Please note that this article was originally published on the Fencepost website via this link www.fencepost-digital.com. We have obtained permission from Fencepost directly to share this article in our blog.

Successfully managing large agricultural fence installations requires a great deal of patience and skill.

Many American Fence Association members are effectively scaling up smaller farm/agricultural fencing jobs to large-size and commercial installations, which is no easy task.

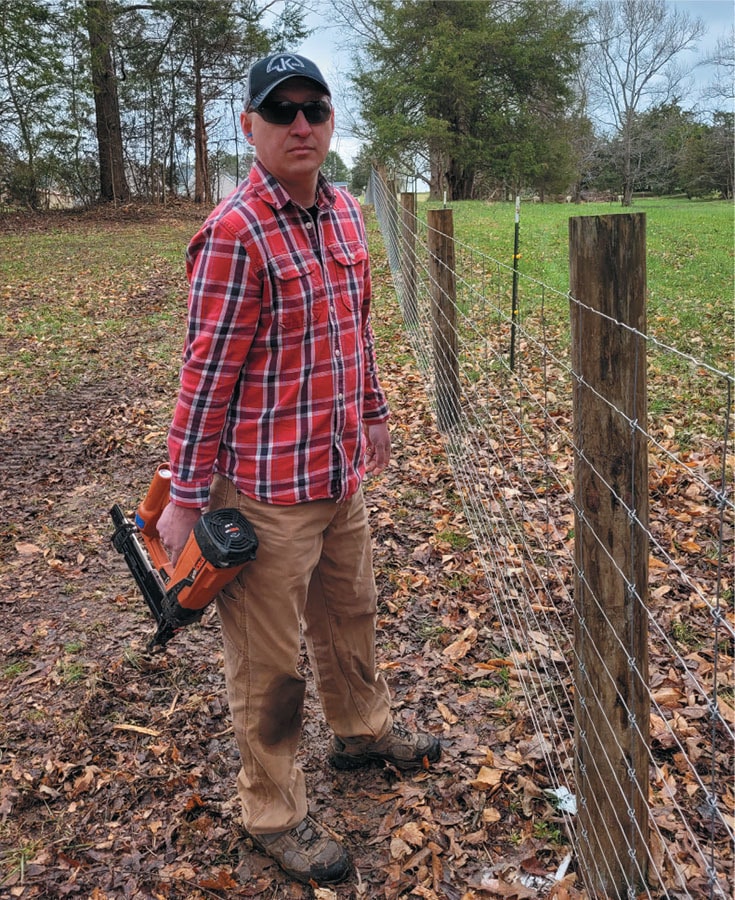

Andy Schoenherr is the Country Manager for the U.S. and Canada working in the agricultural sector at Stockade USA, a division of Illinois Tool Works, which produces staplers and wire fastening systems for rural, commercial, and utility applications not only in the U.S., but Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. He says farm and ag fencing is a very different market than standard commercial or residential fencing.

“Most farm fence contractors grew up on a farm or around agriculture and still enjoy being connected to rural communities. It gets you out of the city or residential areas into more beautiful parts of the country and dealing with a different type of clientele. This also presents a unique set of challenges dealing with the land and types of topography, soil, and environments.”

Andy Schoenherr

For fence contractors just starting out or wanting to increase their knowledge and capabilities, Schoenherr, who is based in Sun Prairie, Wisc., says attending events such as the Fall Fence Forum or East Coast Fence Rivalry can be a great way to learn from other contractors.

“Tool companies like Stockade — as well as the different wire manufacturers and fence post companies — have a lot of amazing people who have been in the business a long time and love talking about fences. Seek out a local fence contractor and ask if you can talk to them or spend a day learning about what they do. People in the farm fence business are extremely generous and really want to collaborate.”

Ryan Sloop is the owner of Sloop Fence, a fencing contractor in Mt. Ulla, North Carolina that specializes in a variety of agricultural fencing services. He started his company in 2012 after looking for diversification in its dairy farming operation.

“Like most fence operations, they grow accidentally, and the learning curve can be steep as the business grows out of our capacity,” Ryan says.

“Ag fence is a type of operation with a different style of clients and challenges completely. These projects require a lot of knowledge in animal safety and building something to put in heavy work around the clock for many years ahead. Tools and equipment are a huge part of our operation. Force multipliers are a tenet of our operation.”

Sloop says a cornerstone of his business has been its track post drivers or fence machines, which have proven to be a very good investment.

“While they may not work for some operations, we would be lost without them. We also run several tracked skid steers and mini excavators. A lot of our best tools are custom made or small tools that cross over from other trades. We also require a power fence stapler that keeps us moving quickly.”

Washington-based Cowboy Construction — formed in 2017 just outside Spokane — specializes in agricultural fence construction. Owner Ryan Gray and his crew work on a wide variety of projects from large ranches to small lifestyle farmlets. He says over the past six years his company has progressed tremendously.

“We have moved to being nearly 80 percent agricultural fencing only. Agriculture is the backbone of our country and to have a small part in this industry brings me joy. Ag fencing is a different skill set than residential and commercial fencing. It’s challenging, and no job is the same.”

He says for those contractors interested in getting into agricultural fencing, he suggests learning from someone who has been in the industry with experience.

“For instance, understanding livestock is important if you are going to build an ag fence. Not only how they move and handle, but safety concerns are very important. Buying the right tools for the job is extremely important as they increase your quality efficiency.”

Types of commercial fencing

When it comes to the type of commercial fencing needed for a project, Schoenherr says it really depends on the market because different parts of the country prefer to put up different styles of fence.

“A lot of projects are smaller farms, hobby or “lifestyle” properties for people who have bought some land outside of town and are looking to upgrade their fencing to handle whatever their preferred livestock may be. That’s really where a fence contractor can set themselves apart with good craftmanship, quality materials and attention to detail.”

He says that in Texas and the Western U.S., one will see much longer runs for large cattle ranches and grazing land.

“Highway and Department of Transportation (DOT) fencing is another major area that some contractors focus on, as well as working with the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS), which is a division of the U.S. Department of Agriculture that subsidizes projects to protect rivers and other waterways from livestock.”

Ryan Gray adds that his team at Cowboy Construction provides a wide range of ag fencing, but his heart remains with the cattlemen and the families that make a living raising cattle.

“I find joy in those projects when we get the opportunity. However, having said that, our best seller is high tensile electric equine fencing.”

Best Practices

When it comes to best practices for getting the job done efficiently and using equipment and techniques to keep costs down and bump profits up, Gray says he and his team run a Protech SB270, a tracked drop weight style post pounder

“This piece of equipment is a one-man operation for setting posts, building braces and more. It reduces our post driving to a one-person job and increases our efficiency tremendously. We’re able to allocate the second and third guy to be onto the next task, either the wire work, laying out, or any number of things that need doing.”

He adds that inadequate post size and depth are two of the biggest issues he sees on agriculture fencing.

“That is, not allowing proper wire tension, so having the right knowledge and equipment allows you to efficiently do that.”

Schoenherr says proper planning and thinking through a project before you start is an imperative best practice as unexpected challenges will always come up.

“Have a plan in place to start each day. Agricultural fence is generally going to be done over a large area, so navigating around the project whether walking, on an ATV or a piece of equipment can be time consuming and detrimental to productivity. If you think through each aspect of the job and when/how it’s going to get done so there’s some flow and organization, it will pay huge dividends over time.”

He also stresses the importance of investing in reliable, quality tools that won’t break down.

“Down time is just wasted money, so you’re better off using quality equipment that you can count on.”

Industry challenges and trends

Access to labor is one of the biggest challenges many contractors face right now as there are simply not enough people available to do the work that needs to be done.

“As a result, everyone has to work smarter and be more efficient,” says Schoenherr.

“Using better technology and the right equipment is the best way to improve productivity. If you can take the pain, strain, and manual labor out of a project by using good quality tools and equipment, you’ll get more work done, be more profitable, and have happier employees at the end of the day.”

For Gray, logistics is the biggest challenge for him and his team.

“Organizing labor, materials, and staging are important to minimizing downtime. Most rural ag jobs are just that, they are rural. For us, one to two hours of travel time is very common. We have to minimize our trips to reduce fuel costs and maximize our time building the fence. This requires planning ahead for each job in relation to its location.”

Sloop adds that logistics is definitely a challenge but part of the job. To help alleviate this, his team will move raw materials from its suppliers to where it will “live” and work.

“Managing a larger project is really not that much more difficult. However, the bigger the shark, the bigger the bite! A big job will bury you faster than it will make you rich! Take is slow and don’t bite off more than you can handle.”

As for trends, Sloop says investing in tools and equipment instead of people seems to be gaining traction.

“It’s also interesting to watch the other side of fencing (residential and commercial) learning how to drive post. The ag business has been doing this for 50-plus years and it’s fun to watch them learn a new practice. I’d like to see more of those guys reach over to the ag world and ask for some pointers.”

Schoenherr adds that there has been a lot of talk about developing minimum standards and best practices around the ag fence industry so that the skilled, quality contractors can set themselves apart from the people doing work that won’t last or hold up as long.

“There are so many different opinions and styles it’s really difficult to get some consensus on that, but the industry seems to be moving in the right direction. Many supply chain issues we saw during the pandemic seem to have eased, so there isn’t as much pressure to get materials. It’s still really hard to find labor. Land prices are at record highs, and inflation and rising interest rates are making it more difficult to acquire and invest acreage for agriculture, so that’s been a challenge as well.”

Two exciting events that Gray thinks are changing the agricultural industry are the Fall Fence Forum in Worthington, Indiana, and the East Coast Fencing Rivalry. Both of these events are dedicated to agricultural fencing.

“This is where contractors can come together to share ideas, and learn from each other with some friendly competition. Events like this help raise the bar for the fencing industry and increase the standard of quality.”

To learn more about our Stockade Ambassadors, please visit www.stockade.com/our-ambassadors.